Quiet Luxury: A Symbol of Exploitation

How insidious is effortless, timeless, sophistication?

Quiet luxury, as we understand it today, consists of a few key elements. Neutral colors and very few prints, an obsession with timelessness, and an absence of logos or other widely legible forms of brand identification. Aided in part by its compatibility with other post-pandemic aesthetics such as the pilates princess, the clean girl, that girl, ballet core, and its similarity to the way many celebrity women are dressed by their stylists (Sofia Richie, Kendall Jenner, Gwyneth Paltrow), quiet luxury has outlasted the typical micro-trend cycle length, enduring now as the sign par excellence of highly sophisticated taste since about late 2022. Several brands, in their focus on high-quality fabrics and almost imperceptible tweaks in the design and construction of normal clothing pieces— think trench coats, denim, shirting— have ridden the wave of popularity to the top: notably The Row, Khaite, and Toteme1

Though many have posited that quiet luxury is a reaction to the more unsophisticated, colorful, exuberant fashion of the 2000s and 2010s, when all the subversion of subcultures slowly became mainstream ways of dressing, I cannot help but wonder if quiet luxury is actually sartorial choice symbolic of a refusal or inability to see things the way they are.

I’m going to sound like the privilege police here, but bear with me for a minute. The women who buy and wear quiet luxury brands are largely white Americans, upper-middle to upper class, who live in metropolitan areas. For the first time since 1989, individuals with high net worth (an annual income of over 250k) account for 50% of all American consumer spending.2 While this spells economic precarity for most Americans, it further cushions the comfortable bubble for this particular consumer group. It seems quite reasonable therefore to venture a guess that most women who purchase mostly (or exclusively) from quiet luxury brands are the very same women who hold the luxury beliefs3 that have done a disservice the American public. These nonpartisan beliefs include the denial of observable sexual and racial difference, the encouragement of mass legal and illegal immigration, defunding the police, Zionism, enabling addiction and subsequent homelessness, and the gullible, wholesale adoption of all new technologies. The natural mimetic nature of a society, in which lower classes or more strongly influenced by the upper class, combined with the enactment of these luxury beliefs via policy has had catastrophic affects on the health and economic stability of the lower to middle-class American, who lacks the financial stability and social network that in part absorbs the negative consequences of these beliefs for their elite counterparts. But white women who buy quiet luxury are no more to blame for the slow, dribbling, demise of America than white men in Ohio overdosing on Fentanyl. My complaint is not against the aesthetic or its adherents, but rather against what quiet luxury has come to symbolize: the exploitation of the consciences of white women against their very own interests.

The fashion industry has always been a bit of a henhouse, but the reign of quiet luxury has solidified its position as an institution that enables the insulation of its primary consumers from plight of those too poor to buy snobby things like high sport pants (catch me DEAD in these, the absolute most unflattering stretchy pants4). The comfort and insulation of these consumers, in turn, makes them a jackpot of money-and-influence for the pet causes of corrupt politicians and lobbyists. The white liberal woman (the luxury fashion customer) has been told her whole life, primarily by a perverted form of feminism5 and unrestricted capitalism, that she can do no wrong, that her own life is the grand narrative, and therefore she need not take any responsibility for her actions. The exploitation of her conscience is possible thanks to her own strange blindness to the female capacity for evil. Her actions are justified by who she is, by the identity given to her by the aforementioned promoters of these luxury beliefs, and she exists at their own gain and at her own expense. What she receives in return is a recurring affirmation of her moral convictions.

Quiet luxury is doing women a disservice. Quiet luxury pacifies and patronizes, it quiets the interior life in a time when this is inappropriate. As I wrote in November, we are ever approaching the time constraint in which our cultural identity can be renewed and revived in a way that befits the grand narrative of American history without nostalgia, or sentimentalism, or hatred, but with a vision for the future that includes past successes and mistakes, integrating those who have joined us on the way. The lifespan in which the luxury beliefs listed above can endure without causing some collapse is nearing the end.

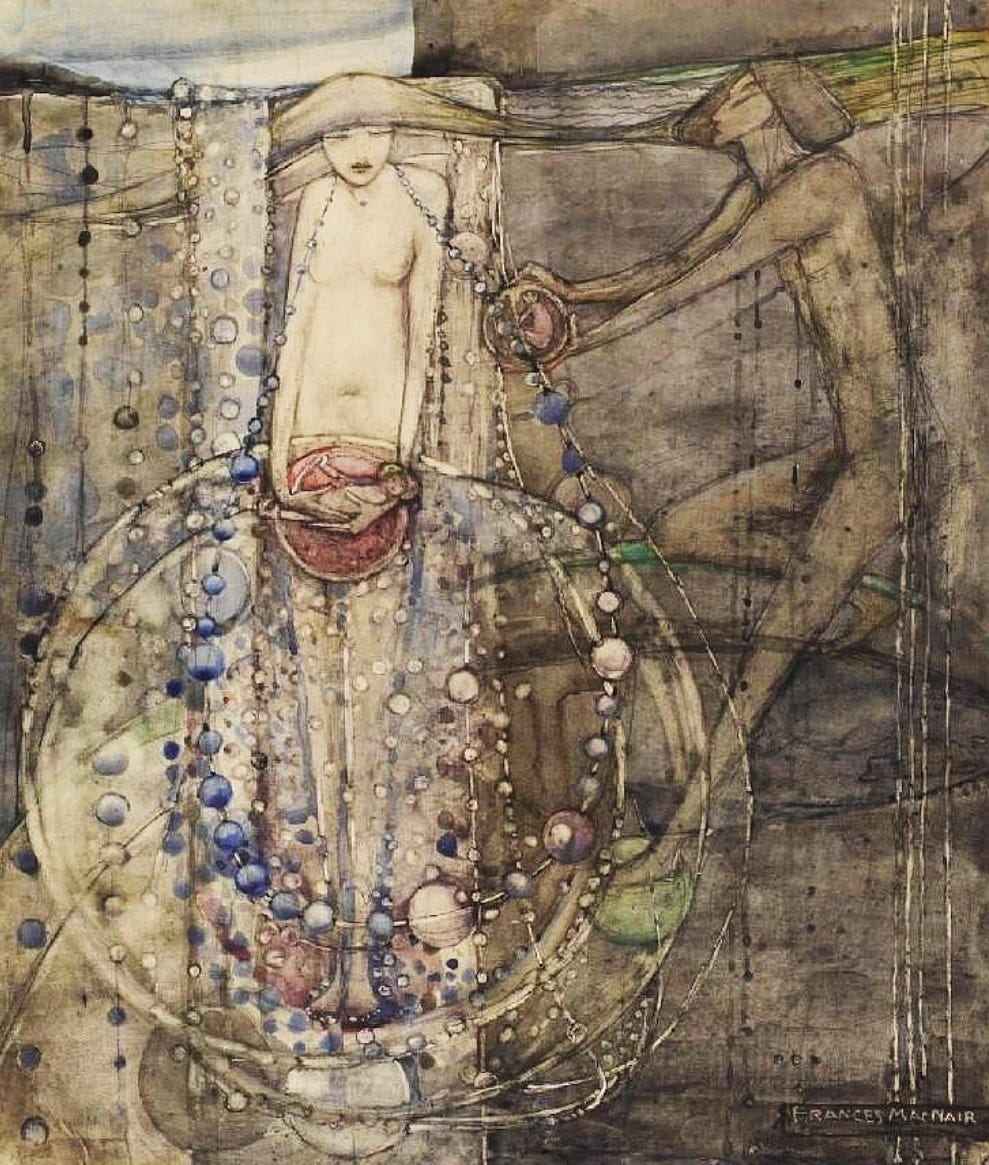

Fashion ought to be a vehicle by which women are awoken from the moral affirmation feedback-loop by which they vote and act against their own interests. The appropriate fashion for a movement such as this is not neutral, devoid of heritage, of the primal and folkloric, of tension between good and evil. No, to erase the tensions and paradoxes of human existence in the name of elegance is bad. I know, I’ve written about beauty in fashion before, here and here. But fashion must also speak to the human condition, it must live in this tension, it must speak of vice, of suffering, of sickness, of unrest, and also of virtue, of joy, of family, of the lovely repetition of daily life. In the aesthetic of a renewed Americana, some provocation and friction is necessary, some identifiable female archetypes must be present, something about the clothing must imbue vitality. Above all, it must be contemporary. It is the privilege of a progressing, advanced, culture to be concerned with timeless things. We have no such luxury, we must reference our time and place in the effort reconstruct a culture sturdy enough to be timeless. As I referenced above, the old subcultures are now dead and sold for parts, but the visionary irreverence of a vigorous subculture should not be underestimated. I can just hardly imagine the ascendant one wearing camel cashmere.

Why care so much about a women’s fashion trend? Because a woman’s existence is more concretely affected by her biology, and likewise through its maternal capacity is more pressingly concerned with the human relationships and generations, the interest of fashion weighs more presently on her mind than on the masculine psyche. Her person is “fashioned as a place in which other souls can unfold.”6 The woman’s body is not a tool to her; therefore her clothes are not just meant to keep her warm, rather they are an important way that she can communicate and perceive the unarticulated realities of her time and place. The divorce between woman and her own biology, woman and motherhood, the pinnacle example of which is the luxury reproductive technology of surrogacy, mirrors the divorce between woman and her country.7 We often speak of living in unprecedented times— this is truly unprecedented; that women have the choice to abandon both their natural privilege to hold their biological children in their own wombs, and also the choice to undermine the sovereignty of the nation in which their children would hope to see happiness and success. In 2025, Andrea Dworkin’s prediction that we would “make the womb extractable from the woman as a whole person”8 has become reality, and by logical extension we have obfuscated her moral obligation to the past and future generations of the very place that she was born. Quiet luxury has emerged as an aesthetic symbolic of the extraction of the white liberal woman from her very own environment, of the exploitation of her conscience for ends that will disrupt the existential happiness of her children.

In the place of neutral and timeless, we need something provocative, something felicitous, something that elevates the consciences and capabilities of American womanhood to the task at hand. May quiet luxury be replaced by fashion that places woman in a true grand narrative, such that her own life regains eternal meaning. For man might make the beads of life, but woman must thread them.9

I’d love to hear in the comments your favorite brands or people with personal style that are outside of this trending aesthetic, or what you think a renewed, contemporary aesthetic of Americana should look like —-

I have nothing personal against the designers of these brands, or against these brands. I like some of what they make, actually. I personally have not bought any clothing from them. They are, however, very good examples of what Quiet Luxury looks like when one buys into the aesthetic wholesale. The same disclaimer goes for the instagram accounts chosen as prime examples of the aesthetic

https://fortune.com/2025/02/27/consumer-economy-ultra-rich-spending/

I am not one of those who would like to throw out feminism entirely

Edith Stein

Don’t construe this to mean that every woman must be a mother, I mean no such thing. Every woman has the potential for motherhood, and her interior life is affected by this potential. Even if she does not have children, she will still desire to embody some sort of spiritual motherhood.

Andrea Dworkin, Right Wing Women pg. 187

This is the name of a painting by Frances MacDonald, pictured above

quiet luxury is the high end version of maoist clothing. devoid of shape and color. expensive sack cloth. you are right and i share your position that women will always give birth to SOMETHING whether it is a real human a great piece of art or the extermination of her countrymen under the guise of not being of this moment. i do like the look of quiet luxury but there would be a coffee wine or tumeric stain on every thousand dollar white t shirt in a heart beat. excellent article!

"It is the privilege of a progressing, advanced, culture to be concerned with timeless things. We have no such luxury, we must reference our time and place in the effort reconstruct a culture sturdy enough to be timeless."

Wow, this really connected a lot of things floating around in my mind. Humanity's obsession with eternity and immortality has never gone away. It's easy to dismiss "quiet luxury" as just another silly trend, but the neuroticism that hides behind it is something I can definitely speak for. Ever since I had become conscious of fashion, it's only ever been anxiety-inducing. In March this year you wrote about "Perfection Exhaustion" and even briefly mentioned quiet luxury there. I was struck by how much this mentality controls my view of fashion and my own embodied existence. My style is currently quite straightforward and simple, bordering on minimalist (though I would hate to use that to describe myself), but I don't see that as the problem. The problem is my obsession with perfection and performance. It doesn't matter whether I'm performing in disheveled layers or a solid color two-piece set, the desperation to remain relevant and "serious" about fashion manifests itself as a tight grip around my throat.

One way I'm trying to combat this is to not overthink my outfits and just have fun with it. More energy should go into contemplating and questioning the "why" of getting dressed, learning about the crafts that encompass fashion, and living life in the time given to us now.

As always, your writing encourages me to do just this! Thank you for another raw and insightful piece.