American women now live perhaps simultaneously the most comfortable and the most exhausting lives possible. Material and physical luxuries abound, we write blog posts weighing the birth of a new (eternal, unique soul) baby into our family versus our potential for future international travel. We carefully consider botox or injectables, Pilates or Barre, Rhode or Rare. We publish essays on how taking the liberty of discarding our children or husbands helped us finally find ourselves.

At the same time, we live in a culture of (nearly) mandatory sexual freedom and self-marketing in exchange for social capital that used to come from more natural things like beauty, class, and character. We write the blog posts and consider the products because we must. We must purchase, we must share, we must perfect. We must accumulate all the possible experiences available to us! We must take all of the paths before us! We must be attractive to every possible suitor, even those who disgust us, everyone must like our photographs, fall asleep to our voices at night. We are slaves to the opportunity cost.

As Mark Grief wrote in his essay “The concept of Experience,”

“Our acceptable philosophy is eudaemonistic hedonism. It says: we act, and choose, and react, by an insatiable hunger for pleasure, and this is to be adjusted, very reasonably, by an educated taste for happiness….

Face-to-face with the shortcomings of more respectable goals, we have turned large tracts of our method of life over to experience—unwittingly. Even where life appears to be lived for happiness, it is lived by and through experience. We see our lives as a collection of experiences.”1 Even our political and religious feelings are justified by our experiences now— as exhibited by the now viral moral circle heat map.

Under the massive compulsion to both accumulate all possible (potentially pleasurable) human experiences while simultaneously performing every moment of your life, women complain that they are “daily dropped in little pieces and passed around and devoured and expected to be whole again next day and all days and …never alone for a single minute,”2 but they are doing this to themselves by the vicious cycle of compelled participation in our culture of perpetual titillation.

Nina Power recently went on Louise Perry’s podcast to discuss the power of images, and they quoted John Berger: “Men look at Women. Women look at themselves being looked at.” Nina observes that with social media, this is particularly true now, and then continues—

“I feel very prudish sometimes when I walk around like Clapham Common or something where you have lots of very young, nice middle class girls… and theyre often wearing… things that are very tight and revealing. And you think, who is this for? Is this for everybody, or is it for a hypothetical other that you are trying to attract? Is it for other women? Is it for the surveillance, there’s a sort of sexy camera? Like, is there a sexy camera on us at all times?”

Right before this tidbit, they discuss women being self-conscious of their appearances even when they are alone. This seems to be a direct consequence of bathing our minds in constant stream of images, of living in a hall of mirrors. Self-surveillance is like doomsday prepping… you have to be constantly ready for “someone” to “see” you. I went through this a little bit myself when I had my first child, because the illusion of control over my body was crushed, my self-surveillance revealed itself through neuroticism about my home. Anytime I sat down to rest or left my house it had to be perfectly clean. I would fantasize about robbers breaking in and being like, wow… it is so clean in here!

Social media has indeed exacerbated woman’s already fraught relationship with surveillance. Returning to the work of John Berger, written pre- social media: “a man’s presence is dependent upon the promise of power which he embodies…. [it] suggests what he is capable of doing to you or for you… By contrast, a woman’s presence expresses her own attitude to herself, and defines what can and cannot be done to her. Her presence is manifest in her gestures, voice, opinions, expressions, clothes, chosen surroundings, taste— indeed there is nothing she can do which does not contribute to her presence…

She has to survey everything she does because how she appears to others, and ultimately, how she appears to men, is of crucial importance for what is normally thought of as the success of her life. Her own sense of being in herself is supplanted by a sense of being appreciated as herself by another.3”

If you accept this generalization of the female experience, it is undeniable that the level of surveillance described here has extended past a performance within polite company to a constant performance, even while alone. You could always be captured on video or ring camera, your husband could see you looking slightly rough one morning and go for someone looking perfect on instagram or pornhub. And many have had their finger on the pulse that women are exhausted. The only people posting on instagram now are influencers, businesses, public personalities, or all three. I saw Katherine Dee, “internet historian,” post just a few days ago, “am I imagining things or does the Internet feel... kind of pointless lately?” Mina Le just put out a video called “why is social media not fun anymore?” Think pieces on ditching your smart phone, spending time outdoors/screen-free/in third spaces abound.

All of this was in the back of my mind as I went on Vogue Runway for a very tardy scroll though the runway shows. I began to screenshot what I was attracted to, what I would actually wear. Before I go on to divulge my findings, I caveat that I have not been posting photos of myself or even taking selfies for 4 years, so perhaps I have healed from social media-induced method acting practices. Regardless, from ages 15-24 I was on social media, and from late 2015 to 2020 I was an instagram addict.

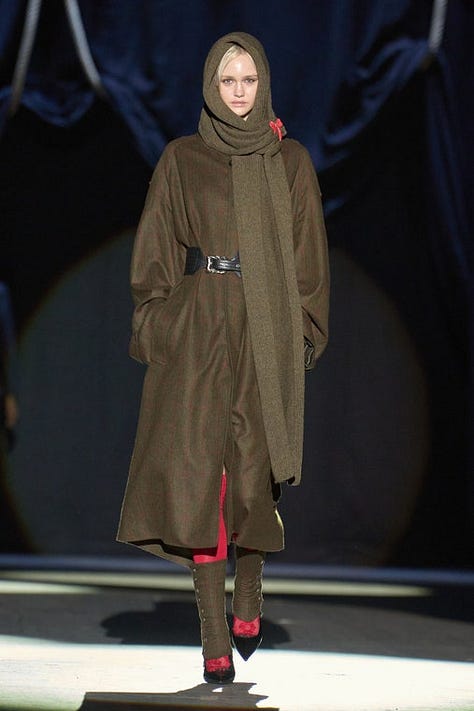

Nothing that I screenshotted was “perfect.” I scrolled through the quiet luxury shows uninspired. In November I wrote about being attracted to brands that emphasized the sleek, tailored, and elegant. This hasn’t disappeared, but it has evolved into what I hoped for: every single image that I saved introduced some element of the disheveled, something off-kilter, something jarring into the balance. Everything felt a little primeval, folkloric; a rejection of decadence. Some element of elegance and echo of great female archetypes remained, but re-imagined.

First of all, such proliferation of hats. I am sure this has been discussed at length in standard trend reports. I cannot help but wonder if the hat is a veil to protect us from the all-seeing eye of the sexy camera. The hat or headpiece or scarf shields one part of our appearance from scrutiny, it allows for the hair to be undone, unwashed even.

The clothes show a deliberate rejection of total self-awareness. The level to which we are self-aware is, I’m sure, unprecedented. I’m so overly self-aware now that when I’m talking to someone else I am conscious of how my face is moving… I never remember this, even in pre-teen days of excruciating self-consciousness, which is a different phenomenon entirely. To be too self-conscious is to be afraid, to be too self-aware is to have constructed a persona for yourself that must always shine through. Textbook main character syndrome.

Simone Rocha, Sacai, Chloe, Brandon Maxwell, Khaite Fur and leather, perennial symbols of protection, warmth, luxury, sophistication— but with the rise of the new right/post left paradigm, now more than ever they are a middle finger to the rules. That and to brands charging hundreds for plastic.

Layering, or what I would call purposeful dishevelment. I think the rise of minimalism was less nostalgia for the nineties and more about what photographed well with an iphone. An outfit with more a complex symmetry, or lack thereof, is difficult to capture. These are clothes for people who “look better in person.” Along with this we see lots of tattered, draped, wet, or soiled things. This isn’t cottage-core, it’s barbaric.

Lots of 80s (and 40s)— in my dreams the 80s are back because they were energetic and vibrant but also because we need a redemption and reversal of the politics of this period. We are harvesting the fruits of this “golden age” as we speak. The 40s…? One can only guess… war-mongering is in the air

Thank you for reading! In 2025, I’m only shopping in-person. The constraint is therefore both my actual available time (not time-warp internet scroll time) and what is there available before me. To that end, I’m going to end each post with a few links of vintage things that have been languishing in my online wish lists and will sell anyways by the end of the year. This week’s are all on etsy because that seems to be my favorite platform (i find it the most “ergonomic”). If you buy anything, send a photo!

White cotton tank by Brunello Cucinelli

Hand embroidered Linen set (Transylvanian costume)

https://www.nplusonemag.com/issue-2/essays/the-concept-of-experience/

Quote is attributed to a housewife, but I think it applies to us all. We are all our own housewives now

John Berger, Ways of Seeing. https://artecontemporaneaeahc.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ways-of-seeing-john-berger-5.7.pdf

I love your subpoint about minimalism. I was into it for a season, but then I realized that a little clutter makes everyone feel more comfortable in real life, be it books on the coffee table, a little dust here and there, layered clothes. As you said, minimalism seemed to eventually become all about the photo ops -- I always find it odd that minimalists are usually still REALLY into photographs. I found myself then needing to take less photos.

the runway looks very aquarian! something classic undone by an awkward weird addition to the look.

i’ve noticed the pluto in aqua girls dress like teen age boys and what feels to me like an effort to protect against being sexualized by.. well advertisers and the sexy camera.