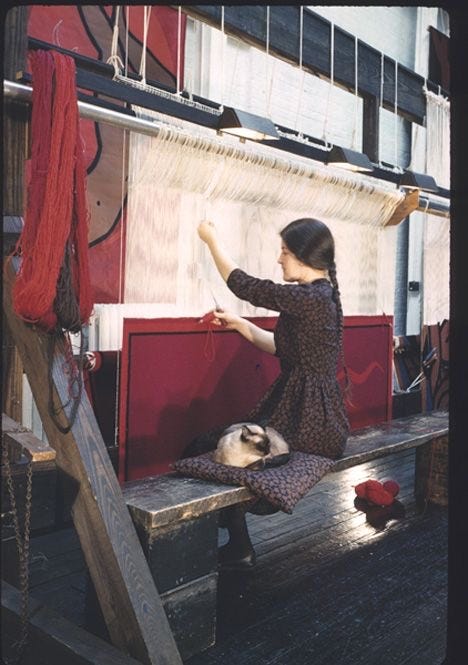

Building, hunting, protecting, these used to be men’s work. Part of the reason we have such a robust record of men’s work throughout the ages can’t just be chalked up to patriarchy or male exceptionalism. It is of course related to male and female biology. Men’s work has historically been heavier, bigger, farther from home. Their work, therefore, involved stones and bones and other things that weather the storms of time rather well. But the ingenuity it takes to build a house of stone is easily comparable to what it takes to go from flax to thread to woven linen of complex patterns and colors. Women’s work was textile work, because it accommodates their biological imperative: breastfeeding (usually up to the age of 2-3 years old) and caring for young children. Judith Brown outlines the five universal parameters for women’s work as 1. easily interruptible 2. repetitive or dull 3. doesn’t require rapt attention 4. doesn’t place children in danger, and 5. doesn’t remove you far from home, forcing you to lug your toddler on your back. These ensure the “compatibility of the pursuit with the demands of childcare.”1 “Most hours of the day were spent fabric making,”2 and it is estimated that for every one hour spent creating a garment, ten hours were spent making the fabric. This was constant work that bled into leisure. I would argue it is now pretty much engrained in the female psyche— fashion being A Principally Feminine Interest and all— and although machines make most of our fabric now, we still have the same need to be clothed.

There are eight different fabrics that can be made mechanically, or by hand, without laboratory ingredients or machines. They are cotton, wool, silk, leather, cashmere, linen, hemp, bamboo. Since the fig leaves these are what have clothed us. When you look in your wardrobe, you might see very little of these, if any at all. Other fabrics go by various names (generic and name-brand), but they are all made from synthetic filaments.

Some of you might be ingredient-label readers (once you start you can’t stop… have you ever checked a box of breadcrumbs? No bread in there). It’s time for you to start reading the “material and care” tab. Take this beautiful dress for example. It says it is constructed from fine merino wool, and the price tag would have you picturing a peasant women at the loom for all of Lent. But under material and care it says it is 95% merino wool and 5% polyamide (name-brand: nylon). So you’re actually paying $2,980 to inhale microplastics. People argue that adding a little nylon to wool increases its durability, strength, and allows it to retain its shape (saving you the labor ironing or steaming), but this just seems to be another case of endless optimization and progress. We can’t just be satisfied with the properties of 100% merino wool (breathable, moisture wicking, UV and fire and odor resistant, anti microbial, hypoallergenic…), we have to add a little allergen back in and pat ourselves on the back for “improving” something that worked just lindy for thousands of years.

Despite the obvious benefits to the environment and subsequent human flourishing, and the appearance, longevity and utility of your clothing, there is an ontological superiority to that which is from dust and to dust will return. Such material things symbolize the purpose of creation and our role of dominion over it. We were created to partake in the life of the Creator, in His life, His goodness, and His providence. God desires that we receive and experience as much of Him as we are capable of receiving in this life. Although our ultimate end is found in beatitude, our own work and fruitfulness on the earth is an anticipatory participation of the kingdom of God. Our dominion over creation is that of stewardship- to take what is there, to care for it, use it for our needs, and allow it to return to the earth. This properly ordered interaction with creation fosters within us both the posture of humility and awe of Providence.

The sort of work that it took to make fabric and garments was not historically one of “supply and demand,” or of economic need. It was, as Josef Peiper defines work, a “happy and cheerful affirmation” of being, of our “acquiescence in the world and in God.”3 Barber notes that although clothes do keep us warm or protect us, the primary reason for clothing, and therefore textiles, is the social fabric of a society. She writes, “most clothing is worn for social reasons— to mark sex, age, marital status, wealth, rank, modesty (whatever that may be within a particular culture), place of origin, occupation, or occasion.”4 And while the legibility and precision of these markers have diminished in our day, these are still the reasons that we wear clothes.

In His Providence, God has provided the material for our clothing in nature itself. Our relationship with the earth is to be symbiotic; as Pope Francis writes, “each community can take from the bounty of the earth whatever it needs for subsistence, but it also has the duty to protect the earth and to ensure its fruitfulness for coming generations.”5 Pope Francis describes how men and women have always intervened with nature, but explains that in the post-industrial age our relationship with the natural world has become “confrontational,” in that “we are the ones to lay our hands on things, attempting to extract everything possible from them while frequently ignoring or forgetting the reality in front of us. Human beings and material objects no longer extend a friendly hand to one another.” Recalling Buber’s concept of I and Thou, it seems that Pope Francis is arguing here that within the Christian worldview there is even potential to view nature as Thou, not in a pantheistic sense, but in familial sense.6 I would be hard pressed to find any sense of Thou in polyester.

To get dressed is to prepare oneself to meet others in the purest sense of the word; to get dressed is to present oneself as we understand ourselves to be in hopes that the other will truly perceive us. The self presented to us in polyester is fundamentally different than the self presented in fiber found in nature. Wool, cotton, silk, leather, linen, bamboo, hemp, cashmere, these place us within God’s creation as co-creators and stewards. They acknowledge the creature as our brother and yet also as our sustenance, with whom we share the fate of death. The process of making these textiles, from raising the sheep or planting the flax, to holding the spindle and building the loom, to cutting and stitching the garment, can be a joyful contemplation of being, a cheerful affirmation of our vocation, our community, and the natural world around us.

But perhaps even more importantly, textile work embraces female embodiment in a special way. In a world where the standard is often masculine, the creation of natural fabrics has always been held to a feminine standard. Elizabeth Wayland Barber often cites her own translations of Homer in her descriptions of Bronze Age textile work:7

By how much the men are expert above all other men in propelling a swift ship on the sea, by thus much the women are skilled at the loom, for Athena has given to them beyond all others A knowledge of beautiful craftwork, and noble minds

The female body, with its maternal capacity, is a symbol of the purest human communion, and therefore woman is more often concerned with the fundamental questions of fashion. It is therefore of the utmost interest, that the maternal capacity of woman is precisely what makes her mistress of the loom. Her creativity and her contemplation must accommodate pregnancy, breastfeeding, small children underfoot. It must accommodate her physical vulnerability in the face of danger by keeping her near the protection of home. This is not restrictive, it is the cadre within which the nobility of the female intellect was able to flourish. Any flourishing (for man, woman, or child) needs the garden walls. Barber shows fantastic examples of the stunning textiles our ancestors were producing in her book Women’s Work.

While we certainly gained much time and convenience from outsourcing fabric and garment making to machines and underpaid laborers (not that we are any better with managing this newfound time), we have exchanged much for this “progress.” We lost the sustainability and healthy ecology that natural fabrics involve. We lost an important connection with nature— the one right against our own skin. And we lost a distinctly feminine form of creativity and contemplation, of stewardship over nature, of handiwork.

I am certainly far from raising my own sheep or weaving my own fabric, but I do take care to read the tags on everything I buy, and I am trying to participate in the “women’s work” of textiles by puttering with some knitting needles and a borrowed sewing machine. I don’t expect to get very good, but it certainly is a contemplative activity (and conducive to the care of young children)!

Proverbs 31:13-25

13 She seeks wool and flax, and works with willing hands. 14 She is like the ships of the merchant, she brings her food from far away. 15 She rises while it is still night and provides food for her household and tasks for her servant-girls. 16 She considers a field and buys it; with the fruit of her hands she plants a vineyard. 17 She girds herself with strength, and makes her arms strong. 18 She perceives that her merchandise is profitable. Her lamp does not go out at night. 19 She puts her hands to the distaff, and her hands hold the spindle. 20 She opens her hand to the poor, and reaches out her hands to the needy. 21 She is not afraid for her household when it snows, for all her household are clothed in crimson. 22 She makes herself coverings; her clothing is fine linen and purple. 23 Her husband is known in the city gates, taking his seat among the elders of the land. 24 She makes linen garments and sells them; she supplies the merchant with sashes. 25 Strength and dignity are her clothing, and she laughs at the time to come.

A few other pieces about natural textile that I enjoyed:

In 2025, I’m only shopping in-person (and natural fibers!). The constraint is therefore both my actual available time (not time-warp internet scroll time) and what is there available before me. To that end, I’m going to end each post with a few links of vintage things that have been languishing in my online wish lists and will sell anyways by the end of the year.

Hand knitted 100% cotton pointelle tank

100% cotton jacket by indie designer Ovate

I have this jacket in chocolate brown

Ralph Lauren silk skirt- 100% cotton-lined

Sonia Rykiel 100% wool brown skirt suit

Judith Brown, “Note on the Division of Labor by Sex.”

Elizabeth Wayland Barber, Women’s Work. Pg. 16

Josef Pieter, Leisure: the Basis of Culture. Pg. 45

Elizabeth Wayland Barber, Women’s Work. Pg. 122

Pope Francis, Laudatory Si. Pg. 44

This brings to mind St. Francis of Assisi’s Canticle of Creation: “Praised be You, O Lord, through all your creatures/ Especially Sir Brother Sun…” and Luke 19:40: “…the very stones will cry out,” Psalm 148, and many more, not forgetting that when God made the world he saw that it was “very good.”

Homer, Odyssey. 7.108-11

Keep coming back to this piece, some lovely thoughts here! I try to only buy cotton/linen/wool/silk when I thrift, and it's really changed my wardrobe. Also, thought you might appreciate this: I'm currently knitting myself my (first ever) pair of socks, out of a lovely 100% wool yarn.

Devils advocate here - I would argue that bamboo and other semi-synthetic rayons aren’t natural fibers due to the chemical processes involved in production. I would also argue that Tencel and Lyocell, specifically the brand names as they are more traceable, would have a more symbiotic nature to them than other rayons. I’m currently experimenting with semi synthetics, I love natural fibers but for some styles they are hard to come by!