Contemplation or Democratization?

How the current system of fashion stifles art and forces us into the marketplace

I’ve been trying to find an antique dress to wear and rewear to some weddings this summer. One is taffeta, made by a home seamstress, with hand-covered scallops and fabric-covered buttons. It is a drop waist, fitted bodice, long sleeved, and a full skirt— for summer (and my excessive arm length) I may have to change the sleeve length. But it is enchanting.

The enchantment lies in the ambiguity of the message. It was made by a singular woman in pursuit of excellence in her craft and in pursuit of a beautiful result. She perhaps was not trying to evoke anything more than the loveliness of the garment and the human form.

As Dominika wrote in her essay on Anna Kamieńska, “When we create art, our art should bear the mark of our person, not artificially or egotistically, but in a way that reminds the creator and beholder that there is someone who endows each of us with our unique personhood—someone who “writes in us”. This is most apparent in the given example of a homemade dress, but it is also possible with entire collections of clothing. Unfortunately, the fashion “industry” as structured today actively prevents and discouraged the designer from being an artist.

Let us first reflect upon a succinct definition of art and also a diagnosis of its current state, given by The Josias:

“There are thus three fundamental points about art: first, that every art concerns something to be made; secondly, that every art is practical, i.e., it is aimed at some activity of life that goes beyond itself, and lastly, in ordinary circumstances every artist hopes to achieve or incorporate beauty into his work, but the pursuit of beauty is subordinate and proportioned to the practical aim of the art itself. The beauty of a piece of furniture should not interfere with its usefulness, and the beauty of music composed for liturgical use should be compatible with its actual use in the celebration of the sacred liturgy. The second and third of these points have been widely forgotten or ignored for the past couple centuries, and the results have not been good for either the arts or for our understanding of them. But nonetheless, these are the points with which a philosophical consideration of art should begin.”

Jacques Mauritian adds to this, “The essential character of art taken in its complete extension is to instruct us how to make something, so that it is constructed, formed, or arranged, as it ought to be, and thus to secure the perfection or goodness, not of the maker, but of the object itself which he makes.”

But if art is intertwined and inseparable from contemplation, as Josef Pieper claims, then through contemplation the artist is perhaps offered a unique path of grace towards comprehending the meaning of existence. For “art flowing from contemplation does not so much attempt to copy reality as rather to capture the archetypes of all that is. Such art does not want to depict what everyone already sees but to make visible what not everybody sees.”1 Art also exists to depict what people wish to avoid seeing but must see to become whole. Both art and contemplation together are essential to the formation of a concrete personhood, and the artist has an important cross to bear on behalf of society in this sense, for they facilitate this conversation.

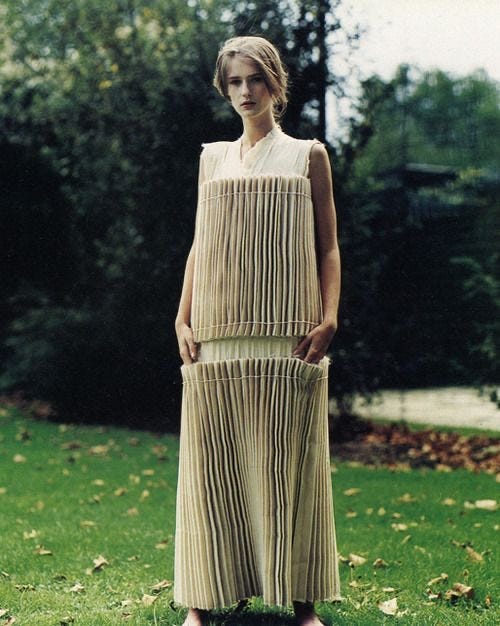

The fashion designer as an artist contemplates, in particular, the human form, fabric, and the various manners in which one can manipulate, shape, and join fabric. His goal is to create something beautiful in that it communicates his own personhood and that of the other who will wear the garment. In this way, fashion is subordinate and proportioned to its practical uses, because it must be used. It is intended for the human body. The attention to precise details and quality that may not be noticed by anyone else is a testament to his respect for art and his treatment of it as contemplation. It is also through this contemplative aspect that the artist’s work must be a work of love. Love for the work itself, and for the goodness of the final result.

But there is an intruder in the quiet of the studio: the market consultant. You want to make clothes? great— here is what people will be buying next year, so get to work. Forget contemplation, there is money to be made.

Trend forecasting is used to predict emerging materials, silhouettes. It bastardizes the work of a clothing designer into someone who makes a product for consumers, not persons. It interferes with the work of the fashion designer as an artist by placing strictures and quotas on their creative process. The artist isn’t necessarily fragile or tyrannical by nature, but they do need the space to find the pulse of their society, understanding the metaphysical undercurrents, in order to create.

In the fashion industry of trend forecasting, the artistic role of the designer is inverted. Instead of leading those who he clothes, he is led by them, it is the logical conclusion of democratic consumption. The question he now answers to is not “what should people wear?,” but “what will consumers buy?” Such a shift makes him justify himself economically, the value in his work is not craftsmanship, quality materials, progress in design, or ingenuity. He is now merely the economic man of fashion. And the people he clothes are deprived of the opportunity to ever approach the “archetypes of all that is” in the experience of wearing his designs.

Some may point to patrons and commissions as evidence that this is a perennial issue within the arts, and since history does repeat itself, there may be some truth to this. All human systems are flawed. However, the ideal execution of the system of patronage is far superior to slavery to the trend forecast. With one you are paid for your talent, discipline, creative capacity, singularity of vision— you contemplate form and material out of a desire to create something, an affirmation of existence, of life as a gift. It is intellectual work and handiwork that involves the intentional cultivation of taste, of putting all things into conversation with one another. What is communicated may be quasi-religious, if not profound.

With the other you are employed for your skill-set, and you are exposed to the temptation to please the most people possible with your “work.” You don’t contemplate— you consult mood boards, data, spreadsheets, market models. You are struggling against existence, taking instead of giving. This is a bastardization of taste and entirely devoid of any coherent philosophy of design or unique soul apparent behind the work. What is communicated is trite if not denigrating: this is the democratization of fashion, what happens when everybody must have access to everything - save the materials, quality, and originality.

When we speak of the common good, we may reflexively think that cheaper, trendy and abundant clothing is better for more people. But this is myopic, because as much as the forecasters and their consumers incentivize SHEIN and the like to produce clothing, they also now seduce some of fashion’s greatest talents away from their God-given path. The problem is not as simple as fast fashion - it’s the problem of mass fashion. Our anti-elite culture wants to always associate the common good with the common man, but this association is a conflation. If “art presumes the social nature of society”2 — well, then turning art (a spiritual good) into purely marketable goods is an exploitation of that society, by dispossessing the common man of a formational, paradigmatic experience of art in order to raise our gdp.

Art of any value must be created with love. Just as the fashion industry no longer glories in the feel, drape, and cut of fabrics, so has the common man lost any nuanced understanding of his need for clothing. He has certainly foregone any chance to discover any beauty that is present and subordinate to its practical use. In the past clothing may have been chosen for “social reasons— to mark sex, age, marital status, wealth, rank, modesty (whatever that may be within a particular culture), place of origin, occupation, or occasion.”3 Now, people either opt out by eschewing any norm of dress entirely, or they wear clothing to mark their availability in our current dominant marketplace: the sexual one. Post sexual-revolution, with norms for both sexuality and interaction between the persons eradicated (although it is impossible to eradicate natural law…), former social reasons for clothes are irrelevant, and clothes are the medium for your success in the sexual marketplace. The packaging and messaging for what is for sale- you! And when you buy clothes, you are buying the way that the clothing company wants you to market yourself to other people. Your purchase, in turn, gives them the data to build their models and predict what you will be buying in 6 months. As Eleanor pointed out in her last essay, there is a a pervasive belittling attitude toward any effort channeled toward the pursuit of art, of beauty, symmetry, form, or interest, in your clothing. The belittlement lies in that, to “non-fashion people,” to put effort towards genuine beauty is seen as a tacit refusal to accept the terms by which we are supposed to dress today: look hot, or not. This is why Leandra Medine Cohen was doing something so subversive with Man Repeller—my introduction to fashion in my early teens. She didn’t care to participate in the sexual marketplace, and therefore trends she followed weren’t the sterile trends of the market. She wrote about the undulations of actual design, and showed us how to step outside the consumer paradigm towards a personal interaction with clothing as art. If the fashion industry is toxic to art and driven by the lust for money, it is no wonder that clothing choices of everyday people are driven by lust.

It is not bad to want to look good. The pursuit of beauty in your own form is part of a properly ordered love of self, part of acknowledging your self-as-gift. But to look good in order to become parts to sell, this is a rejection of the gift of self. This effect on the individual person is directly downstream of the hamster-mill of market forecasting that talented clothing designers are put on. If they are unable to be artists, the common man is stripped of art in his everyday life, and turns to other, more base substitutes. What good clothing ought to do is instruct the wearer in the beauty of his own personhood, inviting him into the conversation that the designer began, in order to “make visible what not everybody sees.”

Josef Pieper, Three Talks in a Sculptor’s Studio: Vita Contemplativa—The Contemplative Life (1985)

https://thejosias.com/2018/01/31/the-philosophy-of-art/

Elizabeth Wayland Barber, Women’s Work. Pg. 122

I loved reading this! I used to work as a stylist and did a bit of styling/consulting for a fast fashion company. I remember once looking around the room filled with people from various departments— production, design, marketing — and I realized that not a single person present actually liked the clothes we were making, no one thought they were beautiful. So much time and resources, and for what! No love! That was the beginning of the end of my fashion career lol

For a few years now I’ve been sewing my own clothes which is a wonderful exercise in contemplation. Making and wearing beautiful things does feel like an affirmation of life as a gift! It increases my awareness of God, my own dignity and the dignity of others, to be dressed in a way that honors Creation. I want this for everyone!!

"What good clothing ought to do is instruct the wearer in the beauty of his own personhood, inviting him into the conversation that the designer began, in order to “make visible what not everybody sees.” I love this!